Cocaine Damage Can Be Misdiagnosed as Nasal Vasculitis

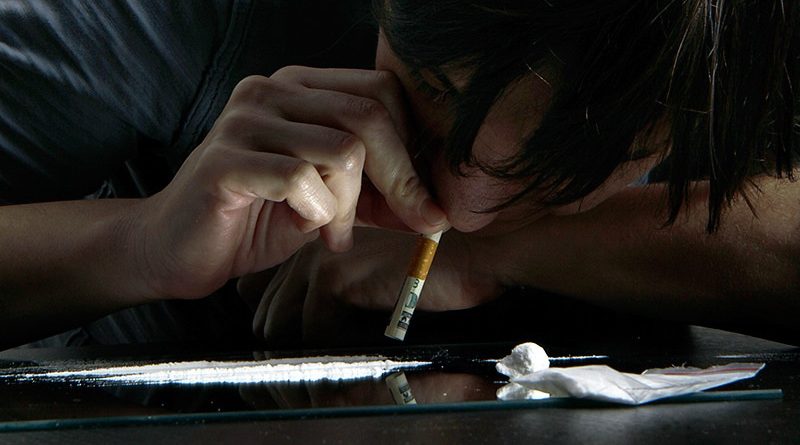

Nasal damage from cocaine use can be misdiagnosed as a rare, nonthreatening nasal disease, according to researchers from the United Kingdom.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), a disorder which causes inflammation in the nose, sinuses, throat, lungs, and kidneys, can have similar symptoms to cocaine-induced vasculitis, the researchers write. Drug testing can help identify patients who have cocaine-induced disease, they argue.

“Patients with destructive nasal lesions, especially young patients, should have urine toxicology performed for cocaine before diagnosing GPA and considering immunosuppressive therapy,” the authors write.

The paper was published in Rheumatology Advances in Practice earlier this month.

Cocaine is the second-most popular drug in the United Kingdom, with 2.0% of people aged 16 through 59 years reporting using the drug in the past year. In the United States, about 1.7% of people aged 12 years and older (about 4.8 million people) used cocaine in the last 12 months, according to the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. The drug can cause midline destructive lesions, skin rash, and other vascular problems, and it can also trigger the production of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) that lead to a clinical presentation that mimics GPA, which can make diagnosis more difficult. Treating cocaine-induced disease with immunosuppressant medication can be ineffective if the patient does not stop using the drug, and can have dangerous side effects, previous case studies suggest.

To better understand cocaine-induced disease, researchers conducted a retrospective review of patients who visited vasculitis clinics at England’s Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham and at the Royal Free Hospital in London between 2016 and 2021. They identified 42 patients with GPA-like symptoms who disclosed cocaine use or tested positive for the drug in urine toxicology test. The study included 23 men, 18 women, and 1 individual who did not identify with either gender. The median age was 41 years, and most patients were white.

Of those who underwent drug testing, more than 85% were positive. Nine patients who denied ever using cocaine were positive for the drug and 11 patients who said they were ex-users also tested positive via urine analysis. During clinical examinations, 30 patients had evidence of septal perforation, of which six had oronasal fistulas. Most patients’ symptoms were limited to the upper respiratory tract, though 12 did have other systemic symptoms, including skin lesions, joint pain, breathlessness, fatigue, and diplopia. Of the patients who received blood tests for ANCA, 87.5% tested positive for the antibodies.

The researchers noted that patients who continued cocaine use did not see improvement of symptoms, even if they were treated with immunosuppressant drugs.

“The experience in our two different centers suggests that discontinuation of cocaine is required to manage patients and that symptoms will persist despite immunosuppression if there is ongoing cocaine use,” the authors write.

Dr Lindsay Lally

“It can feel like chasing your tail at times if you’re trying to treat the inflammation but the real culprit — what’s driving the inflammation — is persistent,” said Lindsay Lally, MD, a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City in an interview with Medscape Medical News. She was not involved with the work.

Lally said the paper had a decent-sized cohort, and “helps us recognize that cocaine use is probably an under-recognized mimic of GPA, even though it’s something we all learn about and talk about,” she noted. She added that routine toxicology screening for patients deserves some consideration, though asking patients to complete a drug test could also undermine trust in the doctor-patient relationship. Patients who deny cocaine use may leave the office without providing a urine sample, she said.

If Lally does suspect cocaine may be the cause of a patient’s systems, she said, having a candid conversation with the patient may have a better chance at getting a patient to open up about their potential drug use. In practice, this means explaining “why it’s so important for me as their partner in this treatment to understand what factors are at play, and how dangerous it could potentially be if I was giving strong immunosuppressive medications [for a condition] that is being induced by a drug,” she said. “I do think that partnership and talking to the patients, at least in many patients, is more helpful than sort of the ‘gotcha’ moment” that can happen with drug testing, she added.

The study authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Lally reports receiving consulting fees from Amgen.

Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2023;7(1):rkad027. Full text

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article