First birth control clinics reduced maternal and infant mortality in the US, study finds

Drawing on an analysis of exceptionally rich historical data, economists from the University of Passau have shown that the birth control and family planning clinics of American women rights advocate Margaret Sanger succeeded not only in reducing birth rates but also had a massive impact on health at the beginning of the 20th century. In so doing, they have provided new insights into the causes and the dynamics of the demographic transition in the US.

In the US, the late 19th and early 20th century saw not only a prohibition of abortions but also a ban on the dissemination of contraceptives and any information regarding sex education. Especially women from the lower income brackets suffered on account of this. Many pregnancies and births put their health at risk and exposed them to the risk of poverty.

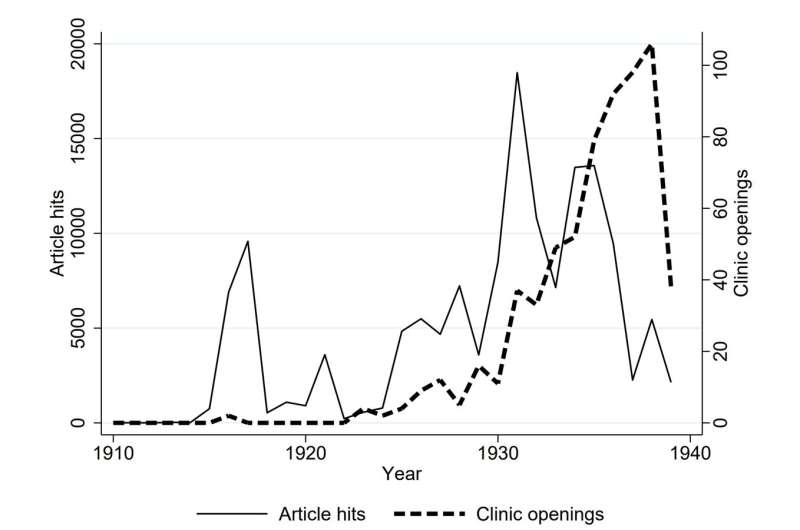

The nurse Margaret Sanger fought against the ban on sex education and for the rights of women. In 1916, she opened the first birth control clinic in New York’s Brooklyn district. Yet, the police shut it down only ten days later, and Sanger was sent to prison. Sanger kept on fighting, started a nation-wide campaign and facilitated the establishment of almost 650 clinics of that kind across the US, especially in the later 1920s and in the 1930s.

The study “The Impact of Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Clinics on Early 20th Century U.S. Fertility and Mortality”—conducted jointly by Professors Michael Grimm and Stefan Bauernschuster, both economists at the University of Passau, in collaboration with US historian Professor Cathy M. Hajo from Ramapo College, New Jersey, U.S.—is the first to examine the impact of these clinics in quantitative terms.

Drawing on the analysis of exceptional historical data, the researchers have demonstrated that the clinics did not only reduce birth rates but also lowered the incidence of stillbirths, infant deaths and maternal deaths: “The results suggest that the clinics prevented births associated with an elevated health risk for the women and children, for instance because pregnancies occurred too soon after previous deliveries or the women generally had already had multiple births. As a consequence, the living and health conditions in the households improved as well,” the economists explain.

The results in summary:

- After a clinic had opened, birth rates declined. Women with some kind of access to a clinic between age 15 and 40 had up to 15 percent fewer children.

- After the opening a clinic, the stillbirth rate decreases by 4.5 percent. This effect is not driven by a decline in the number of pregnancies but can rather be explained by a longer interpregnancy-interval, which improved the health of mothers and the (unborn) children.

- Birth control clinics also resulted in a remarkable decline in infant mortality. Owing to the clinics, 7 percent fewer children died in their first year of life. Again, this effect can be explained by the improved health situation and is not mechanically driven by the decline in the number of births.

- There is also evidence for a decline in maternal mortality. In the period of observation, no sex-specific mortality statistics were published. However, cause-of-death statistics reveal that mortality from puerperal fever declined more strongly in regions with a birth control clinic than in other regions.

Causes of the demographic transition

“We are the first to show that Margaret Sanger’s birth control and family planning clinics actually had a sizeable impact on the demographic transition in the US,” says Professor Grimm.

He holds the Chair of Development Economics and has his research focus on the poorest regions of Africa. For him, the historical US context serves as a kind of field test where some of the findings regarding this period can be applied to the context in the Global South today. His current study builds on a paper in which he had examined the impact of climate conditions at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century on the birth rate in agricultural households using historical US data.

Professor Stefan Bauernschuster, who holds the Chair of Public Economics at the University of Passau, has previously worked with historical mortality data as well. He had demonstrated how the first universal compulsory health insurance under Bismarck had saved lives by disseminating exclusive medical knowledge in the German Empire.

He became intrigued by the work with historical US data as well and the question of how the clinics affected women’s and children’s health: “The impact on the mortality of children in their first year of life is quite remarkable,” says the economist. “We are able to show that the clinics had noticeable health effects.”

For the study, the economists digitalized exceptional data that historian Cathy Hajo had compiled from the Birth Control Reviews published by Sanger, from newspaper archives and from many other sources. The researchers merged this information using data from full-count US censuses and the administrative birth and death records available at city and county level.

US historian Cathy Hajo has extensively researched the life and work of Margaret Sanger. “Margaret Sanger would have been overjoyed had she seen the results of the study,” she says. All her life, the nurse had asked herself whether her advocacy for women had actually made a difference. “We can now show how substantial the impact really was.”

Source: Read Full Article