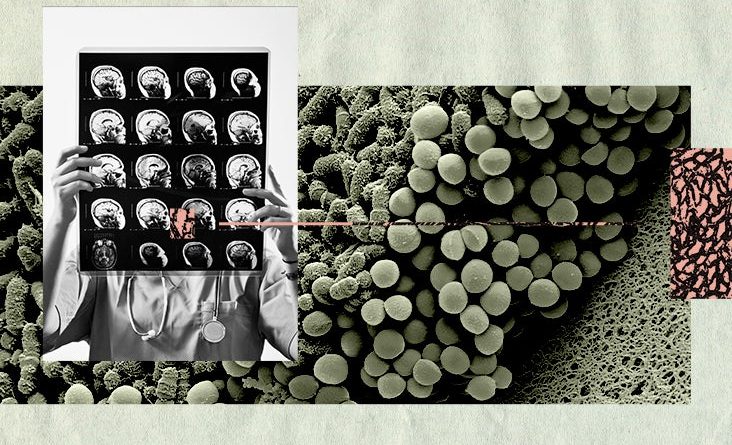

Gut-brain connection: 3 fatty acids may be linked to tau-mediated damage

- There is increasing evidence that people with Alzheimer’s may have different gut microbiomes than people without the condition.

- Experts do not yet know whether these differences in the microbiome are a cause or a result of Alzheimer’s disease.

- New research has shown that altering the gut microbiome changes the behavior of immune cells in the brain in mice.

- The researchers suggest that manipulating the gut microbiome may be a new approach to preventing and treating Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

As the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) continues to increase, the search for ways to treat and prevent it is ever more pressing. Newly licensed treatments, such as aducanumab and lecanemab, that clear beta-amyloid from the brain are a positive development, but they are expensive and controversial.

Many researchers are now focusing on other areas, one of which is the effect of the microbiome — microbes, particularly bacteria, that inhabit the gut — on neurodegenerative disorders.

Now, a new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has found that gut bacteria affect immune responses in the brains of mice.

By changing the gut bacteria in mice that had been genetically modified to develop AD neuropathologies, the researchers altered the amount of neurodegeneration the mice experienced.

The study was published in Science.

The link between gut bacteria and Alzheimer’s

It is widely acknowledged that the microbiome affects overall health, but it is only within the past 15 years that researchers have started to recognize the importance of the so-called gut-brain axis.

“Many diseases of the body and mind are now linked to gut microbiota, including Alzheimer’s disease.”

— Dr. Jennifer Bramen, Ph.D., senior research scientist at the Pacific Neuroscience Institute at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, California

A person’s microbiome changes throughout their life, influenced by environmental and lifestyle factors, such as diet. And research has shown that the microbiome of people with AD has a much lower microbial diversity than that of healthy individuals of similar age, leading to suggestions that there may be a link.

Several studies have suggested how the microbiome might influence the development of neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD. Altered gut bacteria (dysbiosis) may interfere with beta-amyloid clearance, increase the permeability of the gut and blood-brain barrier or alter immune and inflammatory responses.

“There is growing recognition of a gut-brain axis and evidence that the microbiome of individuals varies with disease status. The biggest issue is understanding whether gut changes are due to disease or contribute to disease (or both).”

— Dr. M. Kerry O’Banion, professor of neuroscience at the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rochester

Neurodegeneration from certain bacteria

The mice in this latest study were genetically modified to develop Alzheimer’s-like brain damage and cognitive impairment. All of them carried a variant of the APOE gene, which is a genetic risk factor for AD, and expressed a mutant form of the tau protein that is found in the human brain. The tau protein has been linked to the development of AD symptoms.

The mice were divided into 2 groups. One group was raised in sterile conditions from birth, so did not develop any microbiome, while the others were given antibiotics early in life to permanently change the composition of their microbiome.

All the mice were fed a typical lab diet, although food for the sterile group was autoclaved to destroy any bacteria. They were moved regularly to sterile cages to avoid contamination from old droppings in their cages.

At 40 weeks, researchers euthanized the mice and examined their brains.

The brains of mice that had been kept in sterile conditions from birth showed much less neurodegeneration than the brains of mice with typical mouse microbiomes.

Sex differences

For the mice given antibiotic treatment, there was a difference between the sexes. Male mice showed less brain damage than female mice given the same treatment. This difference was most pronounced in male mice carrying the APOE3 gene variant.

Senior author Dr. David M. Holtzman, the Barbara Burton and Reuben M. Morriss III Distinguished Professor of Neurology, commented:

“We already know, from studies of brain tumors, normal brain development, and related topics, that immune cells in male and female brains respond very differently to stimuli. So it’s not terribly surprising that when we manipulated the microbiome we saw a sex difference in response, although it is hard to say what exactly this means for men and women living with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders.”

3 fatty acids may be culprits

The researchers found that three short-chain fatty acids produced by certain types of gut bacteria were linked to neurodegeneration.

These fatty acids were absent in mice with no microbiome and at very low levels in those that had been given antibiotics. The researchers suggest that these fatty acids were activating immune cells that damaged brain tissue.

To test this, they fed these three fatty acids to middle-aged mice with no microbiome. Their brain immune cells then became more active, and their brains subsequently showed more signs of tau-linked damage.

Potential treatment for AD

The findings offer insights into how the microbiome might influence tau-mediated neurodegeneration in humans. The researchers suggest that modifying the gut microbiome with antibiotics, probiotics, specialized diets, or other means might be a new approach to preventing and treating neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD, in people.

“Many researchers believe that work aimed at unpacking the complex influence of the gut microbiome on Alzheimer’s disease will lead to new therapeutics to prevent and mitigate neurodegeneration.”

— Dr. Jennifer Bramen

There is increasing evidence that a healthy microbiome benefits many aspects of human health. This new study suggests that looking after your microbiome might also lower your risk of developing AD and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Dr. O’Banion said that the current study “helps establish causality and bring hope that modifying the human microbiome might impact health by preventing or altering diseases.”

However, the findings must be treated with caution as mouse models cannot exactly replicate the disease in humans. But the researchers believe that this study opens avenues for further research.

“What I want to know is, if you took mice genetically destined to develop neurodegenerative disease, and you manipulated the microbiome just before the animals start showing signs of damage, could you slow or prevent neurodegeneration?”

— Dr. David Holtzman

Source: Read Full Article