Mexico City Policy on global aid curtailed family planning services in Africa, study finds

A new study has found that the Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance policy, formerly known as the Mexico City Policy, reduced the provision and use of contraceptives, as well as community health volunteer services, in African countries.

A Trump administration policy barring United States funding to foreign organizations that perform or promote abortion services has had detrimental effects on family planning service delivery and utilization in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a new study led by Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH).

Published in the journal Science Advances, the study found that the Mexico City Policy, which was reinstated and expanded in 2017 by the Trump administration as the Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (PLGHA) policy, substantially reduced the supply and usage of contraceptives in African countries highly dependent on US global health assistance.

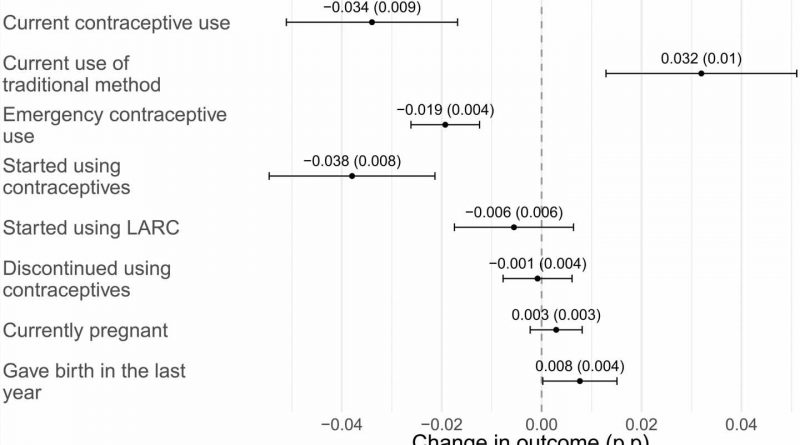

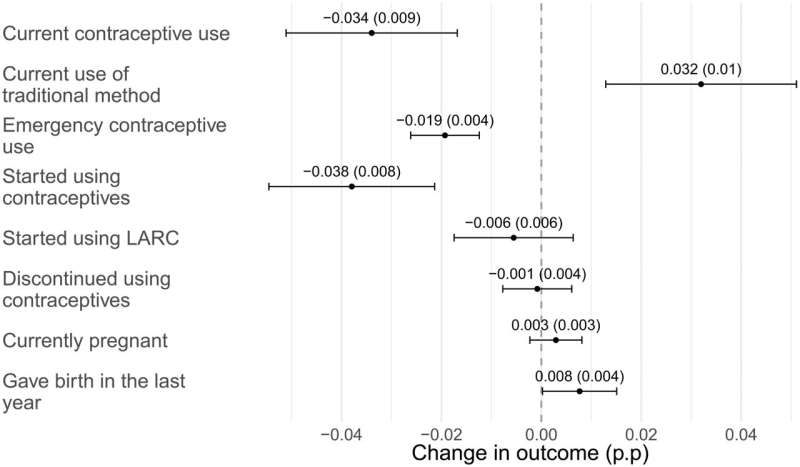

Following the implementation of PLGHA, health facilities provided fewer contraceptives and women were less likely to use contraception and more likely to have given birth recently under the policy.

The former Mexico City Policy is a Reagan-era policy that, when in effect, restricts international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from discussing, promoting, or advocating for abortion as a family planning service in order to receive US funding.

Since its inception in 1984, the policy has been rescinded and reinstated by presidential administrations along party lines. The Trump administration expanded this policy beyond family planning programs to pertain to nearly all US global public health assistance, including programs for HIV/AIDS, maternal and child health, malaria, global health security, and more.

Previous research has focused primarily on individual health outcomes of the policy, including increased abortion rates; this new study sheds light on how political decisions around US international aid can curb women’s access to community-level health services and, in turn, affect their family planning and health.

“By reducing both the provision and utilization of family planning services, PLGHA impinged on the autonomous decision-making of health providers and women,” says study lead and corresponding author Dr. Nina Brooks, assistant professor of global health at BUSPH.

A likely consequence of this policy is the further exacerbation of health inequalities, Dr. Brooks says. “We see similar reductions in the provision and utilization of family planning among providers and women in countries more reliant on US global health assistance. These parallel effects make it increasingly clear that these changes are due to the implementation of PLGHA.”

For the study, Dr. Brooks and colleagues from Stanford University and the University of Minnesota analyzed high-frequency survey data from health facilities and women in eight African countries that are reliant on US global health assistance, from 2014 to 2019. The researchers compared health outcomes and service delivery before and after PLGHA took effect under the Trump administration, distinguishing between countries that are more and less reliant on US funding for global health.

In countries more reliant on funding, the researchers found that this policy reduced provision of all family planning methods by 6 percent but certain methods were more heavily affected. For example, emergency contraceptive service provision was reduced by nearly 30 percent, compared to less reliant countries.

Community health volunteer programs—and the short-acting contraceptive services that they provide—were also more likely to be curtailed in countries more vulnerable to funding restrictions. These programs are critical for reaching women in remote areas, where they would otherwise have difficulty accessing health services.

Women in countries more vulnerable to funding restrictions were also less likely to be using any form of modern contraceptives and appeared to substitute with use of traditional methods. When PLGHA was in effect, women in these countries were also more likely to have given birth recently, resulting in a 5.7% increase in births compared to women in less reliant countries when PLGHA was not in effect.

“The goal to reduce abortions, especially unsafe abortions, is widely shared,” says study co-author Eran Bendavid, associate professor of medicine and health policy at Stanford School of Medicine. “However, what we show is that putting constraints on organizations that provide family planning and contraception is an ineffective—and often counterproductive—approach to improving the health and well-being of young women.”

The detrimental impact of PLGHA on family planning and women’s autonomy around reproductive health also lends worrying implications for other health programs and outcomes: congressional reauthorization talks for the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), have stalled as Republicans lobby to apply PLGHA to the generally bipartisan HIV/aids initiative, claiming that it supports abortion providers. Democrats and health experts refute this claim and say that the delayed reauthorization threatens to hinder critical lifesaving support for HIV/AIDS.

“This research provides further evidence of the unintended consequences of the MCP/PLGHA, as the purpose is to reduce abortion, not contraceptives,” Dr. Brooks says. “As we head into another presidential election cycle, it is critical to remember the impact that US politics and policy have on the lives of women worldwide.”

“These are important findings about a major US policy which should matter regardless of one’s views about abortion,” says study senior author Grant Miller, Henry J. Kaiser, Jr. Professor at Stanford School of Medicine. “Our hope is that they can be understood that way.”

More information:

Nina Brooks et al, U.S. global health aid policy and family planning in sub-Saharan Africa, Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adk2684

Journal information:

Science Advances

Source: Read Full Article