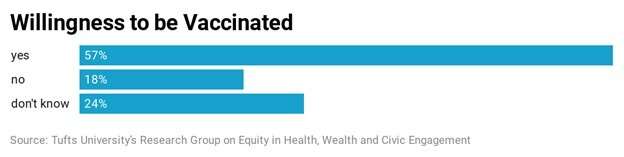

Only 57 percent of Americans say they would get a COVID-19 vaccine

Despite widespread agreement among experts that having a prophylactic COVID-19 vaccine will be critical to the nation’s ability to safely return to some form of normalcy, only 57% of Americans say they would get a COVID-19 vaccine if it were available today, according to a national survey designed and analyzed by Tufts University’s Research Group on Equity in Health, Wealth, and Civic Engagement.

The nationally representative survey also uncovered significant variations in vaccination acceptance by race/ethnicity, household income, educational background and party affiliation. Whites and Hispanics, Democrats, those with more formal education, and those with higher incomes reported being more likely to get vaccinated than Blacks, Republicans, those with less education, and those with lower incomes. Fully one-quarter of respondents said they didn’t know if they would get the vaccine, possibly indicating the need for more public health education and information.

“It’s really concerning that only 57% of our respondents said they would get vaccinated. It’s evident that we need to begin working on a national vaccine strategy and education campaign right now—even before we have the vaccine in hand,” said Jennifer Allen, professor of community health in Tufts University’s School of Arts and Sciences and co-leader of the study. “There is still some uncertainty, but some studies show that we need between 60 and 70% of the population to be vaccinated in order to confer herd immunity.”

There has been growing resistance to all vaccines in the U.S. over the past decade, which has led to reduced compliance with vaccine recommendations and the re-emergence of diseases like measles and mumps, which were previously well-controlled. Growing anti-vaccination sentiment has been fueled by misinformation about vaccines, including the widely de-bunked theory that vaccines could cause autism.

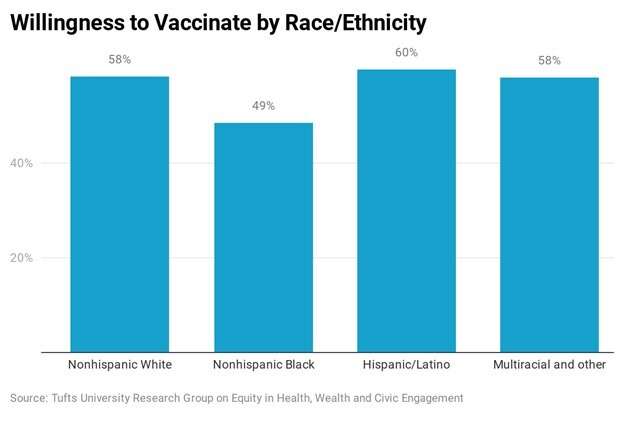

Whites and Hispanics more likely to vaccinate

The study also revealed marked differences of opinion toward vaccination across racial groups, with 58% of non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics reporting they would get the vaccine as compared with 48% of non-Hispanic Blacks.

“The pandemic has disproportionately affected Black individuals,” said Allen. “The lower level of vaccine acceptance within this population is worrisome, as it suggests the vaccine could further exacerbate COVID-19 racial/ethnic disparities. Given the legacy of medical experimentation on African Americans, there is understandable mistrust in medical science and in government.”

Allen continued, “The accelerated time-frame for vaccine development and testing could further raise concerns about the safety and efficacy of an eventual vaccine. Targeted efforts will be needed to make sure that a vaccine doesn’t further widen the gap in health outcomes.”

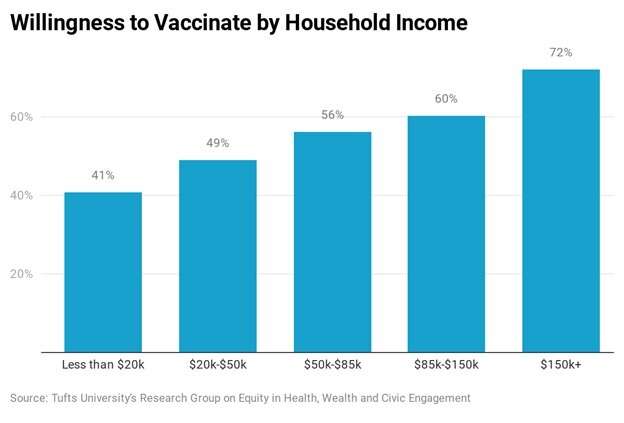

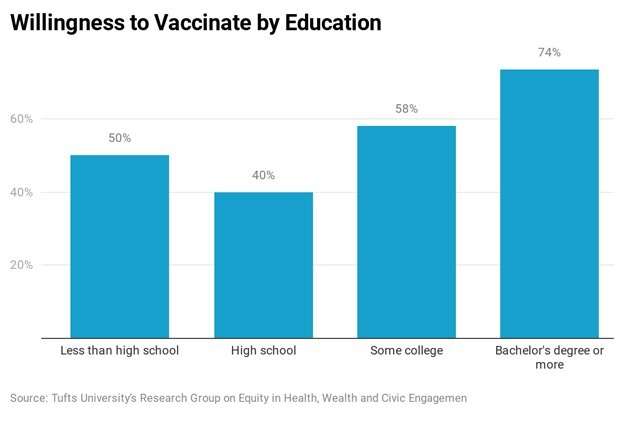

Income and education plays factor

Surprisingly, those with higher levels of income and education were more likely to report that they would get the COVID-19 vaccine. “Historically, those most likely to refuse vaccines have been those with higher levels of income and education,” said Allen.

Among those with incomes less than $20,000, only 41% said they would get the vaccine, compared with 72% among those with incomes of $150,000 or more. Less than half of those with a high school education or below said they would get the vaccine, compared with 74% among those who had a college education.

Differences across political parties

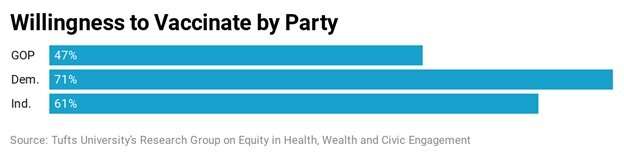

Sharp polarization by political party affiliation also emerged in the responses. Willingness to be vaccinated was highest among Democrats (71%) compared with Independents (61%) and Republicans (47%).

“Differences between political parties are striking. As with many aspects of the pandemic, vaccination is a highly partisan issue,” said Peter Levine, an associate dean at Tufts’ Tisch College of Civic Life. “The partisan gap may pose an obstacle to widespread vaccination.”

While public health officials, clinicians and pharmaceutical companies race to develop a COVID-19 vaccine, it is evident that, should a successful vaccine become available, distribution and administration will need to be accompanied by health communication, promotion and education campaigns, said Tom Stopka, an infectious disease epidemiologist and associate professor with the Tufts University School of Medicine, and a co-leader of the study. “Such campaigns can help to increase understanding of how the vaccine will work, decrease doubts and mistrust of local, state, and federal officials, and potentially demonstrate that the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh the risks.”

Stopka added, “The U.S. population has been overwhelmed with COVID-19 information and stress, as well as massive changes to their day-to-day lives. When and if a vaccine becomes available, and has been thoroughly tested in human populations, it will be necessary to also develop a massive public health communication campaign to provide community members with the information they need to make an informed decision to protect themselves, and to protect their families and local communities.”

Source: Read Full Article