Three-dimensionally reconstituted organoids that are just like human organs

Organoids are organ-like tissues derived from stem cells that are grown in labs, often referred to as miniature organs. Because they can imitate the structure and function of human organs, they are considered a next-generation technology for creating artificial organs or developing new drugs. Recently, a research team in Korea introduced a new concept of mini-organs called assembloids that surpass these organoids to structurally and functionally replicate human tissues. These findings were announced on December 17 (KST) in Nature, one of the most prestigious journals in science and technology.

A team led by Professor Kunyoo Shin of POSTECH’s Department of Life Sciences has developed multi-layered miniature organs called assembloids that precisely mimic human tissues by three-dimensionally reconstituting stem cells together with various cell types in tissue stroma. The assembloid is a novel, innovative technology that can present a new paradigm for the next-generation drug discovery of intractable diseases as patient-customized human organs that transcend the conventional organoids.

Organoids are miniature organs that are similar to human organs. However, the current organoid technology has a fundamental limitation in that it cannot mimic the mature structure of organs and lacks the microenvironment within the tissues. Furthermore, critical interactions between various cells within the human tissues is lacking. This limitation has been considered a major issue in precisely modeling various intractable diseases including cancer.

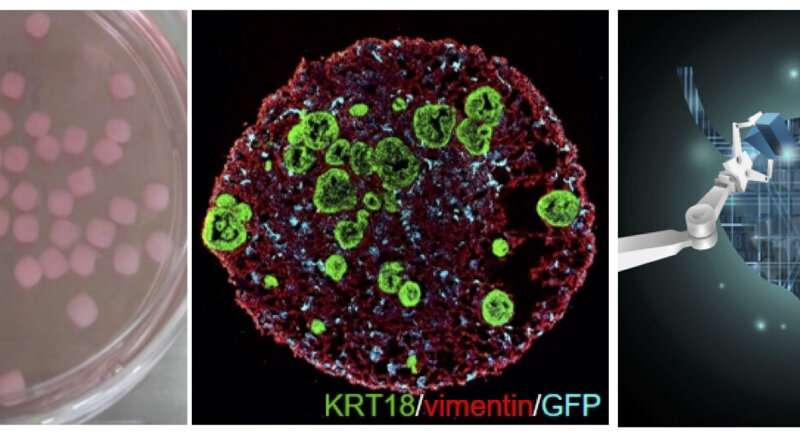

To overcome these limitations, Shin’s team developed reconstituted in-vitro human organs called assembloids, which have organized structures of epithelial cells, stromal layers, and outer muscle cells. The researchers found that these assembloids were identical to mature adult organs in terms of cell composition and gene expression at the single cell level, and that they mimic the in-vivo regenerative response of normal tissues to the injury.

In addition, the team developed patient-specific tumor assembloids that perfectly mimic the pathological characteristics of in vivo tumors. Using this tumor assembloid platform with genetic engineering technologies, the team revealed the novel mechanisms in which the signals from the tumor microenvironment determines the plasticity of the tumor cells. These findings show that the signaling feedback between the tumor and stromal cells play a critical role in controlling the tumor plasticity. This discovery will lead to a novel paradigm in the development of cell differentiation therapy for the treatment of various aggressive types of solid cancers.

“These assembloids are the world’s first in-vitro reconstituted organoids,” explained Eunjee Kim, the first author of the paper. She added, “We can precisely model a variety of complex intractable diseases such as cancer, degenerative diseases, and various neurological diseases including schizophrenia and autism, and understand the pathogenesis of such diseases to ultimately develop better therapeutic options.”

“To our knowledge, our efforts to generate assembloids that structurally and functionally recapitulate the pathophysiology of original tissues have not been previously described,” commented Professor Shin who led the study. He added, “Generating such artificial tissues is particularly relevant to modern research because the importance of tissue microenvironments in epithelial tissue homeostasis and the growth of various tumors is increasingly being recognized. We anticipate our study to open a new era of a drug discovery that will revolutionize the advancement of patient-customized treatment for various intractable diseases.”

Source: Read Full Article