Using a robotic shoulder to grow tendon tissue

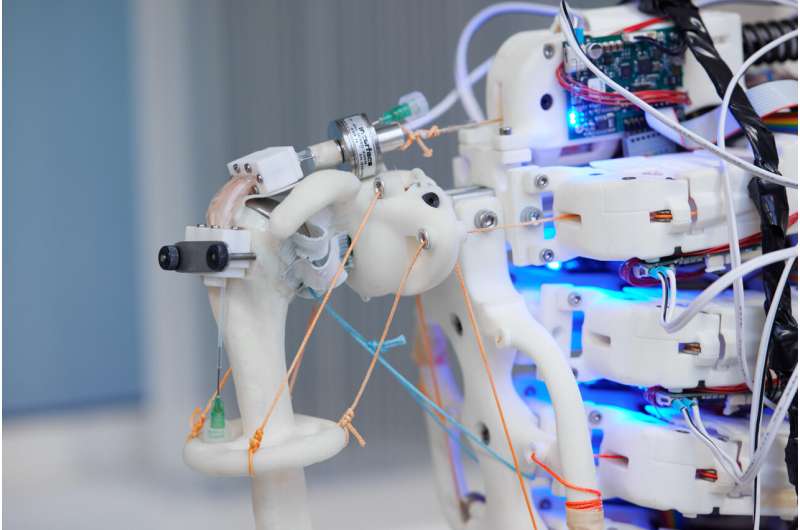

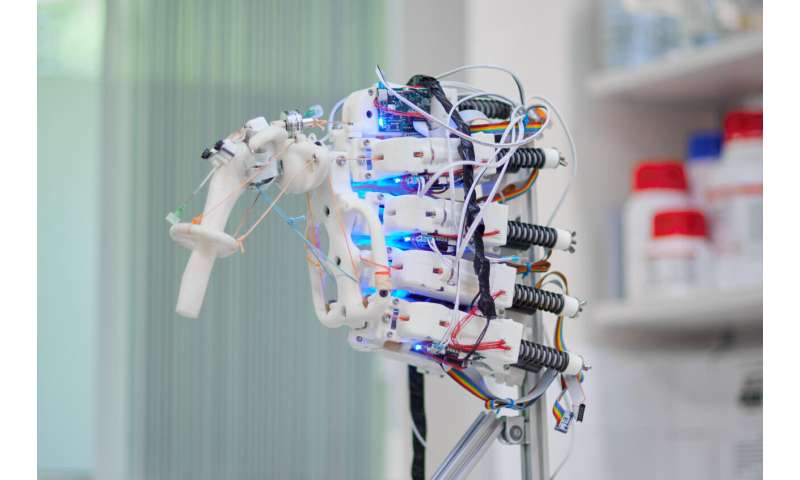

A team of researchers from the University of Oxford and Devanthro GmbH has modified a robot shoulder to serve as a stretching mechanism in an effort to grow useful human tendon tissue. In their paper published in the journal Communications Engineering, the group describes modifying the robot shoulder and using it as a bioreactor to grow human tissue.

Over the past few decades, medical scientists have been investigating the possibility of using fibroblast cells to grow human tissue that can replace tissue lost or damaged in human patients. To that end, researchers have grown organs, skin, cartilage, and even a windpipe. But such endeavors are still in their infancy.

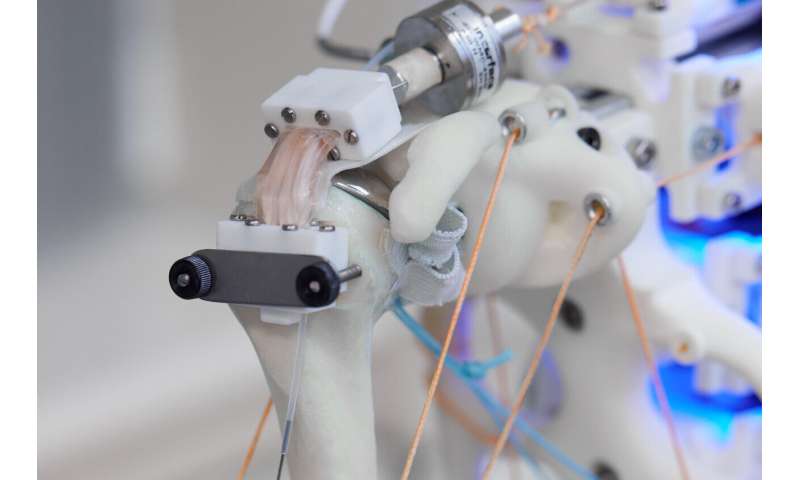

One area of research that has proven to be particularly challenging is growing tendon tissue. Previously engineered tissues have lacked the elasticity required for use in a human patient. Attempts have been made to increase elasticity by building devices that stretch and bend the tissue as it grows. Unfortunately, these attempts have not produced tissue that can bend, twist and stretch to the degree real tissue can. In this new effort, the researchers have taken a new approach. Instead of cultivating tendon tissue in boxes with devices that pull on it, the researchers grew it in a more human-like way—on a fabricated joint made to mimic a human shoulder.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=wd4YPsIh7h0%3Fcolor%3Dwhite

The researchers began their effort by modifying an open-source robot developed by engineers at Devanthro to allow for the addition of a bioreactor and a means to attach the new tissue as it grew. Once the bioreactor and hair-like filaments were in place on the robot shoulder, the team flooded pertinent areas with nutrients to stimulate growth. The cells were then allowed to grow over a two-week period, during which the shoulder was activated for 30 minutes each day, bending, pulling and twisting in human-like ways. At the end of the growing period, the researchers studied the resulting tissue and found that it was different from tissue grown in a static environment—but they still do not know if the tissue is an improvement on other methods. More work is required to determine if the newly grown tissue might be a close enough match to the real thing for use in human patients.

Source: Read Full Article