dizziness with buspar

California is the only state in the U.S. with a statewide tax for mental health programs, applying to personal incomes above $1 million. Approved by voters in 2004, the tax has generated over $20 billion since 2005. But has the infusion of mental health funding made a difference?

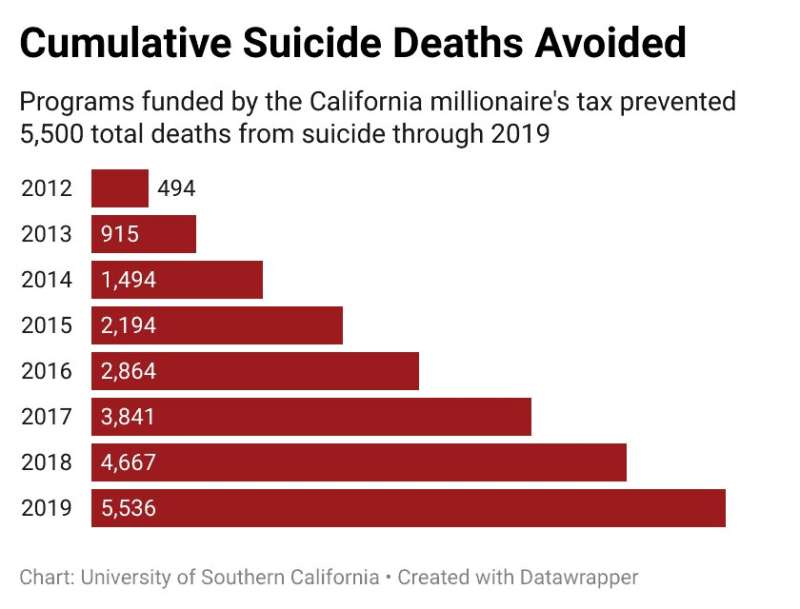

Published today in PLOS One, a new peer-reviewed USC study is the first to examine whether revenue from California’s mental health tax affected a vital public health indicator: suicide. Authored by Michael Thom, associate professor at the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy, liability insurance in pharmacy the study shows programs funded by the tax prevented 5,500 total deaths from suicide between 2005 and 2019.

Reducing suicides is a pressing issue given that the U.S. suicide mortality rate increased by over 30% from 1999–2019.

Thom used the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System data to determine how the millionaire’s tax affected deaths by suicide in the state, developing a “parallel version of California” to predict what would have happened without the tax. The largest number of suicide deaths—approximately 870—was averted in 2019, the final year studied.

Millionaire’s tax led to different mental health results among various age groups and genders

The study showed not all groups experienced the same benefits from the more robust mental health services funded by the millionaire’s tax. For example, the male suicide rate is triple that of females. Moreover, the study found that women’s suicide mortality rate decreased significantly more than it did among men. The reduction in female suicide mortality in California in 2019 was 29% compared to the 17% reduction among males.

Thom was most surprised by the finding that older people experienced a larger reduction in suicide deaths than younger people. Adults aged 55–65 years and those over 65 years old had some of the largest and most consistent reductions in suicide deaths.

“So much of what we hear in the media is the increase in suicide or suicidal thoughts among younger people,” said Thom, who points to the fact that it’s now the second leading cause of death among individuals under 34. “Disappointingly, this tax doesn’t appear to have moved the needle when it comes to reducing suicide deaths among younger adults.”

Thom theorizes that older adults can more easily accommodate inpatient and outpatient care than younger adults because they are less likely to be tied to fixed employment schedules and domestic responsibilities. People over 65 may also benefit from Medicare’s mental health services.

The study results go only through 2019; since that time, mental health struggles have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, making it even more critical to evaluate the effectiveness of policies like California’s.

“California is pioneering a new approach to mental health. Studies like this are necessary to identify which groups are benefiting from the policy and to go back to the drawing board to make sure all groups, whether it’s by gender, age, or race, see some benefit from this,” Thom explained. “After all, this wasn’t a millionaire’s tax to improve mental health among retirees; it was to improve mental health, period.”

Thom suggested several changes that could improve earmarked mental health taxes and associated programs, including more responsive programs that address challenges unique to racial and ethnic groups and that address male-specific concerns. He also called for improved access for younger adults, especially 15- to 34-year-olds, which may include integrating mental health care services into high schools and colleges, expanding the availability of paid time off from work to receive treatment, and access to mobile app-based diagnostic and treatment tools.

How should California fund mental health services?

While the revenue source isn’t the focus of the study, Thom pointed out that the income of California’s wealthiest citizens—and therefore the amount of money generated from a tax on that income—can be volatile. The study shows that during the Great Recession, the revenue collected from the millionaire’s tax dropped dramatically. The economy eventually rebounded, and by 2012, the money collected and used for California mental health programs began to make a difference in the state’s suicide deaths.

Thom suggested state lawmakers should consider a different revenue source. “Everyone thinks a millionaire’s tax is a great idea when the economy is thriving, but if you want this public good to continue, California should use general funds for these mental health programs,” he said.

Source: Read Full Article