Charles Dickens wrote about the diphtheria crisis of 1856—and it all sounds very familiar

A strange and frightening disease is killing people around the world. Medical opinion is divided and it’s very difficult to get an accurate picture of what is going on. The authorities are trying to avoid a panic, travel has been disrupted and fake news is rife. All this was happening when Charles Dickens picked up his pen in August, 1856, to write a letter to Sir Joseph Olliffe, physician to the British embassy in Paris.

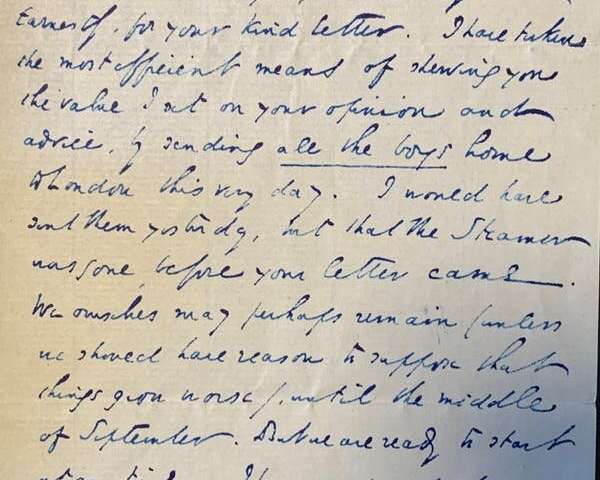

I recently discovered the letter during my research into the great writer’s lifetime of correspondence. In it, Dickens thanked the doctor for alerting him to an outbreak of diphtheria in Boulogne-sur-Mer on the coast of northern France while he was on holiday there. Three of the writer’s sons were actually in school there at the time and were getting ready for the new term. Dickens told the physician: “I have no doubt of our being in the healthiest situation here, and in the purest house. Still, if you were to order us off—we should obey.”

Diphtheria was then little known and referred to by the public as “malignant sore throat,” “Boulogne sore throat,” or “Boulogne fever.” Its scientific name, diphtheria, was conceived by Pierre Bretonneau and referred to the leathery membrane that develops in the larynx as a result of bacterial infection. It was dangerous, contagious and often fatal. The disease spreads in the same way as COVID-19—by direct contact or respiratory droplets.

In the letter, Dickens highlighted the case of Dr. Philip Crampton. He was on holiday in Boulogne at around the same time as Dickens when two of his sons, aged two and six, and his 39-year-old wife all died within a week of each other of diphtheria. Dickens wrote: “I had no idea of anything so terrible as poor Dr. Crampton’s experience.”

With the spread of the contagion across the channel from France to England, scientific investigations accelerated and by 1860—four years after its first detection in England—the history, symptoms and communicability of the disease were more fully understood.

Boulogne was then a favourite haunt of the English, who numbered 10,000 (a quarter of the population) in the 1850s. Dickens liked the town which he called “as quaint, picturesque, good a place as I know,” because he could remain relatively anonymous. He could enjoy the pleasant summer weather which was conducive to his work. Boulogne could be reached from London in about five hours, via the train and the ferry from Folkestone, which sailed twice daily.

He wrote portions of “Bleak House,” “Hard Times” and “Little Dorrit” there and made it the focus of his journalistic piece, “Our French Watering-Place,” published in his journal Household Words. Dickens developed a warm relationship with his French landlord, Ferdiand Beaucourt-Mutuel, who provided him with excellent accommodation—both in Boulogne and, in later years, in the hamlet of Condette, where he had installed his lover, Ellen Ternan, in a love nest.

Dickens must have been worried by accounts of the “Boulogne sore throat” in the press and so sent his sons home to England for safety. French medical authorities played down the extent of the infection, which unfortunately coincided with an outbreak of typhus that killed Dickens’s friend, the comic writer and journalist Gilbert Abbott À Beckett. À Beckett had also been holidaying in Boulogne and—in another tragic twist—as he lay mortally ill, his son Walter died of diphtheria two days before he himself was taken by typhus.

In a letter to The Times on September 5, 1856, a group of prominent Boulogne physicians noted that “with a very few exceptions, this disease has been confined to the poorer quarters of the town and the most indigent of the population.” A few days later, on September 12, a person calling himself “Another Sufferer from the Boulogne Fever” wrote to the paper to say that he had been staying in the same boarding house as À Beckett and that his wife had caught diphtheria. He concluded his letter by pleading: “If you can spare any of your valuable space for this letter, it may also be of service to warn persons who intend to cross the channel to Boulogne.”

Misinformation

This prompted another letter from the Boulogne medical authorities, on September 16, challenging the assertions of “Another Sufferer” and pointing out that the “panic” was “almost entirely confined to temporary visitors”—even though the physicians admitted: “Most assuredly we would not advise any one to take a child” to “a house where malignant sore throat had recently existed.” Misinformation about the epidemic was rife: boarding houses and travel companies continued unreservedly to advertise Boulogne as a holiday destination. Even the hotel where À Beckett died covered up the true cause of his death.

As a journalist himself, Dickens was highly sensitive to fake news. In his letter to Olliffe he observed: “We have had a general knowledge of there being such a Malady abroad among children, and two of our childrens’ little acquaintances have even died of it. But it is extraordinarily difficult … to discover the truth in such a place; and the townspeople are naturally particularly afraid of my knowing it, as having so many means of making it better known.”

In 1856, those who were cautious and prudent stood a better chance of survival and eventually life did return to normal for Dickens. His sons went back to school in Boulogne and he would return many times.

Source: Read Full Article