Depression and Insomnia: clinical treatments for a common comorbidity

By Keynote ContributorDr. Alexander SweetmanPostdoctoral Research Fellow at the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health

Given these strong sleep-mood relationships, it is not surprising that insomnia and depression frequently co-occur. For example, up to 90% of people with depression experience sleeping problems, and up to 50% of people with insomnia report depressed moods. Indeed, insomnia is one of the core diagnostic symptoms of depression, and poor mood is commonly included among ‘daytime functional impairment’ diagnostic criteria for chronic insomnia.

Co-occurring insomnia and depression result in significant morbidity for patients and difficult diagnostic and treatment decisions for clinicians. Bi-directional relationships between sleep and mental health can make it difficult to determine the most appropriate treatment approach when a patient presents with both conditions. Hence, it is important to consider the high comorbidity, consequences, and management approaches for co-occurring insomnia and depression.

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder, characterized by difficulties falling asleep, staying asleep, and/or early morning awakenings during the night and associated impairments in daytime feelings or function. Approximately 50% of adults report acute (short-term) insomnia symptoms, and 10-15% of adults fulfill diagnostic criteria for ‘chronic insomnia disorder’ (lasting for at least three months). Chronic insomnia is associated with reduced mental health and quality of life and incurs substantial economic costs through healthcare use and reduced productivity.

Image Credit: TheVisualsYouNeed/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: TheVisualsYouNeed/Shutterstock.com

Historically, when insomnia has occurred in the presence of other physical and mental health problems, it has been conceptualized as a ‘secondary symptom.’ This position assumes that there is little purpose in directly treating sleeping difficulties, as the comorbid condition would cause them to re-emerge soon after treatment. Furthermore, it is assumed that successful management of the ‘primary’ condition (e.g., depression) would alleviate the insomnia complaint.

However, a large body of evidence over the past two decades challenges this outdated conceptualization of ‘secondary insomnia.’ It is now known that insomnia is one of the most consistent risk factors for the onset of future depression, insomnia and depression share bi-directional relationships, untreated insomnia can contribute to relapse of depression after treatment, and that targeted treatment of insomnia disorder also improves mental health.

Consequently, it is important to increase the availability of insomnia diagnostic and treatment options for people with and without comorbid mental health problems and for clinicians to consider targeted assessment and treatment approaches for both insomnia and depression when they co-occur.

Insomnia is often an independent and chronic condition

Although short-term insomnia can initially result from other mental and physical health problems (e.g., depression, pain, etc.), insomnia symptoms can rapidly develop functional independence of these initial causes. Insomnia can become a self-perpetuating condition maintained by insomnia-specific underlying cognitive, behavioral, and physiological mechanisms. For example, it is common for people with acute insomnia symptoms to extend the time they spend in bed to acquire more sleep. However, this more commonly results in extended time spent awake in bed.

Image Credit: Qualit Design/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Qualit Design/Shutterstock.com

Suppose sleep has already become a source of anxiety or frustration. In that case, this results in an increased amount of time in bed feeling worried, frustrated, or annoyed at failed attempts to sleep and concerns about the potential effects of lost sleep on daytime functioning. Over repeated occasions, a conditioned relationship can quickly form whereby the bedroom routine or bedroom environment can become the trigger for this physiological and cognitive arousal response. Some behaviors such as canceling daytime activities or napping during the day can further exacerbate sleeping difficulties. In this scenario, the insomnia symptoms persist even after the initial precipitant is treated or abates (e.g., depression, pain).

Multiple nights of interrupted or broken sleep and time spent awake feeling frustrated or worried can cause impaired daytime feeling and functioning and gradually reduce quality of life. For this reason, insomnia co-occurring with other physical and mental health problems should be conceptualized as a functionally independent ‘comorbid’ condition.

Insomnia treatments are effective in the presence of comorbid depression, anxiety, and stress

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for insomnia (CBTi) is the most effective and recommended first-line treatment for insomnia. Although sedative-hypnotic medicines (e.g., benzodiazepines) result in acute improvements in sleep, they are not recommended as a long-term approach to manage insomnia because of the potential for negative side-effects, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms. CBTi is a multi-component therapy that aims to identify and target the underlying causes of insomnia. While sedative-hypnotic medicines result in rapid relief from insomnia symptoms, CBTi results in gradual improvements sustained long after treatment is complete. CBTi commonly includes four to eight weekly/fortnightly sessions delivered by a trained therapist in-person, via telehealth, or in small group settings. CBTi programs have also been adapted to self-guided online or reading materials.

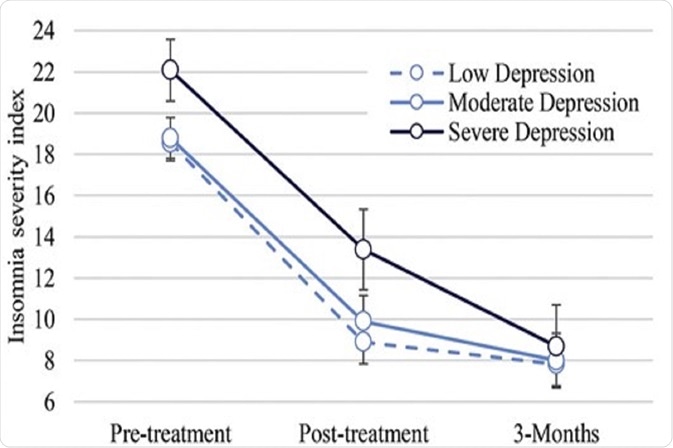

We recently used data from a large sample of patients with chronic insomnia managed in a specialist insomnia clinic at the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health to investigate the effectiveness of CBTi in patients with different levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. Approximately 50% of the 455 patients reported at least mild depression symptoms before treatment. There were large and sustained reductions in insomnia following CBTi, and there was no difference in insomnia improvements between patients starting treatment with low, moderate, and severe depression symptoms (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Among patients with chronic insomnia, there was no difference in the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia between patients starting treatment with low, moderate, and severe depression symptoms. Figure adapted from Sweetman et al., (2020).

Figure 1: Among patients with chronic insomnia, there was no difference in the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia between patients starting treatment with low, moderate, and severe depression symptoms. Figure adapted from Sweetman et al., (2020).

Treating insomnia improves depression symptoms

Meta-analyses have reported that CBTi programs (including self-guided online programs) improve insomnia, depression, and anxiety symptoms in patients with co-occurring insomnia and mental health problems. This suggests that treating insomnia symptoms may be a useful treatment option in patients presenting with comorbid insomnia and depression that may be used in addition to targeted treatments for mental health problems.

Improving access to behavioral insomnia treatment

It is important to increase access to evidence-based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for insomnia (CBTi) worldwide. Although CBTi is recommended as the most effective and first-line treatment for insomnia, few health professionals have specific training and expertise in CBTi delivery. For five consecutive years, the RACGP Health of the Nation report has found that psychological issues, including sleep disturbance and depression, are the most common reasons people present to a general practitioner. Consequently, it is important to provide GPs with the information, assessment tools, treatment, and referral options to manage co-occurring depression and insomnia.

The Department of Health recently confirmed that general practitioners can refer patients with insomnia to a psychologist with a Mental Health Treatment Plan. There is a great opportunity to provide additional training to existing psychologists and postgraduate psychology students in delivering CBTi. Furthermore, interested GPs may also deliver a brief behavioral treatment for insomnia during four to five weekly/fortnight GP appointments. There are also evidence-based online insomnia treatment programs available in Australia, including a current trial of Sleepio (developed in the UK), a four-session insomnia program offered through This Way Up (Managing Insomnia), and an online mindfulness insomnia treatment program (A Mindful Way).

Where can readers find out more information?

The Sleep Health Foundation has published several fact sheets to guide conceptual models and management approaches for comorbid sleep and mental health problems and information about specific sleep disorders such as insomnia, circadian rhythm disorders, and obstructive sleep apnoea.

About Dr. Alexander Sweetman

Dr. Alexander Sweetman is a postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health and the Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute: Sleep Health, Flinders University. He is involved in a National Centre for Sleep Health Services Research that aims to understand and improve the management of sleep disorders in Australian primary care.

Dr. Alexander Sweetman is a postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health and the Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute: Sleep Health, Flinders University. He is involved in a National Centre for Sleep Health Services Research that aims to understand and improve the management of sleep disorders in Australian primary care.

References

- Sweetman A, Van Ryswyk E, Vakulin A, et al. Co-occurring depression and insomnia in Australian primary care: a narrative review of recent scientific evidence. Medical Journal of Australia. 2021;215(5):230-236.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed, DSM-V). 2013.

- Reynolds A, Appleton S, Gill T, Adams R. Chronic insomnia disorder in Australia: A report to the Sleep Health Foundation. Sleep Health Foundation Special Report. 2019.

- Baglioni C, Battagliese, G., Feige, B., Spiegelhalder, K., Nissen, C., Voderholzer, U., Lombardo, C. & Riemann, D. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;135(1-3):10-19.

- Natsky A, Vakulin A, Chai-Coetzer C, et al. Economic evaluation of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for improving health outcomes in adult populations: a systematic review Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2020;54.

- Lichstein KL. Secondary insomnia: A myth dismissed. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2006;10(1):3-5.

- Gebara MA, Siripong N, DiNapoli EA, et al. Effect of insomnia treatments on depression: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Depression anxiety. 2018;35(8):717-731.

- Ye Y-y, Zhang Y-f, Chen J, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i) improves comorbid anxiety and depression—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142258.

- Spielman AJ, Caruso, L. S., & Glovinsky, P. B. A behavioral perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatry Clinics of North America. 1987;10(4):541-553.

- Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:869-893.

- Spielman AJ, Saskin, P., & Thorpy, M. J. Treatment of chronic insomnia by restriction of time in bed. Sleep. 1987;10(1):45-56.

- Bonnet MH, & Arand, D. L. Hyperarousal and Insomnia: State of the Science. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2010;14(1):9-15.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, Part B: Benzodiazepines. 2015.

- Ree M, Junge M, Cunnington D. Australasian Sleep Association position statement regarding the use of psychological/behavioral treatments in the management of insomnia in adults. Sleep Medicine. 2017;36:S43-S47.

- Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2016;165(2):125-133.

- Sweetman A, Lovato N, Haycock J, Lack L. Improved access to effective non-drug treatment options for insomnia in Australian general practice. Medicine Today. 2020;21(11):14-21.

- Sweetman A, Lovato N, Micic G, et al. Do symptoms of depression, anxiety or stress impair the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia? A chart-review of 455 patients with chronic insomnia. Sleep Medicine. 2020;75:401-410.

- Haycock J, Grivell N, Redman A, et al. Primary care management of chronic insomnia: a qualitative analysis of the attitudes and experiences of Australian general practitioners. BMC Family Practice. 2021;22(158):1-11.

- RACGP. Health of the Nation: Summary Report. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP): Health Profession Health Australia. 2021.

- Meaklim H, Rehm IC, Monfries M, Junge M, Meltzer LJ, Jackson ML. Wake up psychology! Postgraduate psychology students need more sleep and insomnia education. Australian Psychologist. 2021:1-14.

- Sweetman A, Zwar N, Grivell N, Lovato N, Lack L. A step-by-step model for a brief behavioural treatment for insomnia in Australian General Practice. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2020;50(50):287-293.

- Sweetman A, Knieriemen A, Hoon E, et al. Implementation of a digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia pathway in primary care. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2021:106484.

Further Reading

- All Insomnia Content

- Insomnia – What is Insomnia?

- Insomnia Causes

- Insomnia Symptoms

- Insomnia Treatment

Disclaimer: This article has not been subjected to peer review and is presented as the personal views of a qualified expert in the subject in accordance with the general terms and conditions of use of the News-Medical.Net website.

Last Updated: Nov 8, 2021

Source: Read Full Article