Human Monkeypox – Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, Diagnosis, and Prevention

Introduction

The global monkeypox outbreak of 2022

Transmission of monkeypox virus to humans

Cross immunity and protection

Clinical features

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Prevention

References

Further reading

The human monkeypox virus, which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus of the family Poxviridae, is a double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) virus. As of June 9, 2022, over 1,000 people have been confirmed to be infected with the monkeypox virus in nearly 30 countries around the world.

Image Credit: FOTOGRIN / Shutterstock.com

The global monkeypox outbreak of 2022

Although the monkeypox virus is endemic in several African countries, its incidence has generally remained quite low in these nations. However, the last two decades have evidenced an exponential rise in the number of human monkeypox cases, surpassing the statistics accrued over the initial 45 years since its first discovery.

There are two genetic clades of the virus that include the West African and Central African clades. Although all confirmed monkeypox cases from the current outbreak have been confirmed to belong to the West African clade, none of these cases have been associated with travel to an endemic area.

Rather, these cases have been primarily, but not exclusively, identified in men who have sex with men (MSM) who were seeking healthcare services in primary and sexual health clinics. Nevertheless, the extent of local transmission of the monkeypox virus during the current outbreak remains unclear due to current limitations in its surveillance. Global healthcare organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) anticipate that additional cases of monkeypox infection will be identified in non-endemic countries.

Since transmission of the monkeypox virus is typically a rare occurrence in individuals without any travel history to an endemic area, there is an urgent need to quickly identify and isolate infected individuals, as well as to conduct efficient contact tracing, to limit further transmission of this virus.

Importantly, previous reports have indicated that infection with the West African clade typically causes less severe disease as compared to the Central African (Congo Basin) clade. Moreover, the fatality rates of these clades are estimated to be 3.6% and 10.6%, respectively.

To date, there has not been a single death reported in the current monkeypox outbreak. Nevertheless, since the WHO expects that additional monkeypox cases will be identified in the future, it is essential that countries around the world initiate efficient surveillance strategies to mitigate the further spread of this virus.

These efforts should also involve increasing awareness of the current outbreak to potentially affected communities. Furthermore, some countries may also want to consider administering smallpox vaccines to individuals who have been in close contact with an infected individual, as well as prophylactically for certain vulnerable populations, such as healthcare workers.

Transmission of monkeypox virus to humans

The infection spillover of the monkeypox virus to humans remains obscure. While aerosol transmission has been confirmed among animals, direct or indirect contact with infected animals or their carcasses has been implicated in animal-to-human transmission events. Aerosol transmission also poses a threat to veterinary professionals and hospital staff.

Rodents are often hunted for food, as they provide a protein-rich dietary alternative to the poor. Unfortunately, these animals are carriers of the monkeypox virus.

The incidence of monkeypox infection is typically highest among people living closer to forests and in regions where the smallpox eradication programs had been tapered off as a result of the waning cross-immunity among the unvaccinated and lower age groups. These mechanisms have been implicated in escalating the number of human cases in Central and West Africa.

Another primary contributing factor to the human spillover of monkeypox infection is the increasing contact of humans with small mammals. For this, invasion of forest areas, civil wars, refugee displacement, deforestation and cultivation, climate change, demographic changes, and population shifts are to blame.

This pathogen can invade through breached skin, respiratory tract, or mucous membranes. Homan-to-human transmissions are also not uncommon through respiratory droplets or contact with body fluids, lesions, contaminated surfaces, or fomites.

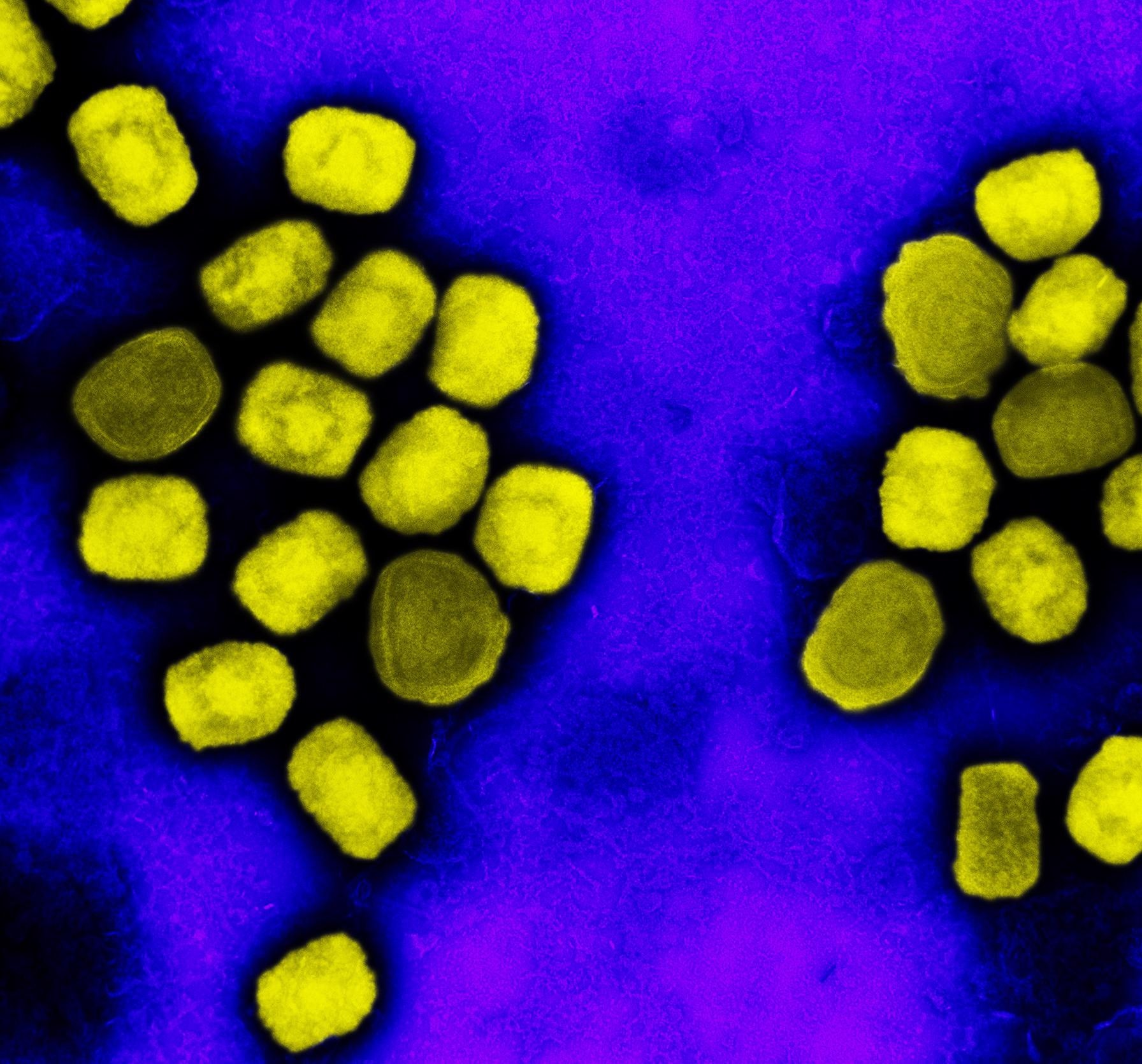

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of monkeypox virus particles (yellow) cultivated and purified from cell culture. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of monkeypox virus particles (yellow) cultivated and purified from cell culture. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Cross immunity and protection

Vaccinia virus vaccines protect against monkeypox disease. Moreover, the neutralizing antibodies generated by these vaccines are responsible for the primary immunologic mechanism of such cross-protection. Apart from humans, even monkeys benefit from smallpox vaccines, as they offer protective effects against monkeypox disease.

Widespread induction of smallpox vaccines was withdrawn in 1978. Thereafter, cross-protective immunity against orthopoxviruses has declined, especially amongst the younger generation who remain unvaccinated and susceptible to these viruses. It is likely that these factors contribute to the increased number of cases and further transmission of the virus.

Clinical features

The clinical signs and symptoms of this infection are identical to those of smallpox in regard to its onset, duration, and sites of the skin involved.

The incubation period for the monkeypox virus is between five and 21 days, with symptom duration typically lasting for two to five weeks. The characteristic features of infection with the monkeypox virus include fever, chills, lethargy, asthenia, headaches, backaches, myalgia, and lymph node swellings.

A rash is a primary symptom of this infection, with lesions of varying sizes that typically begin to appear on the face and subsequently spread across the body. The rash transforms into macules, papules, vesicles, and then pustules, and usually resolves with crust and scab formation, which spontaneously exfoliate on recovery. Areas of erythema and skin hyperpigmentation are also common.

Image Credit: Berkay Ataseven / Shutterstock.com

Additional symptoms of this infection are inflammation of the pharyngeal, conjunctival, and genital mucosa. Clinically, the symptoms and lesions are milder and indistinguishable from smallpox. However, the mortality rate is 1-10%, which could be more significant in children and immunocompromised adults.

Complications of infection with the monkeypox virus can include secondary infections, respiratory distress, encephalitis, a corneal infection that can cause vision loss, as well as gastrointestinal involvement, which can include vomiting and diarrhea with dehydration. The clinical presentation of individuals infected with the monkeypox virus who have not received smallpox vaccination is more severe and associated with higher mortality.

Differential diagnosis

The distinction between chickenpox, monkeypox, and herpesvirus infection remains clinically challenging during outbreaks. As a result of the non-specific signs of monkeypox infection, several other diseases and conditions must also be ruled out. These may include molluscum contagiosum, bacterial skin infections, scabies, syphilis, measles, rickettsial infections, anthrax, and drug reactions.

The lesions of the monkeypox infection differ from those in chickenpox in their distribution and extent of skin invasion, which is more significant with monkeypox lesions. Furthermore, the lesions of chickenpox tend to appear denser on the trunk rather than spreading throughout the face and extremities as in monkeypox. A clinically differentiating sign of monkeypox infection is lymphadenopathy.

The diagnosis of this infection is often based on clinical signs and investigations. These include viral culture of oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal swabs and laboratory analysis of skin specimens and exudates from the lesions.

Other diagnostic methods can include skin biopsies, electron microscopy culture and molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing, serologic testing for monkeypox-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) or IgG detection, as well as histology and immunohistochemistry of the lesions.

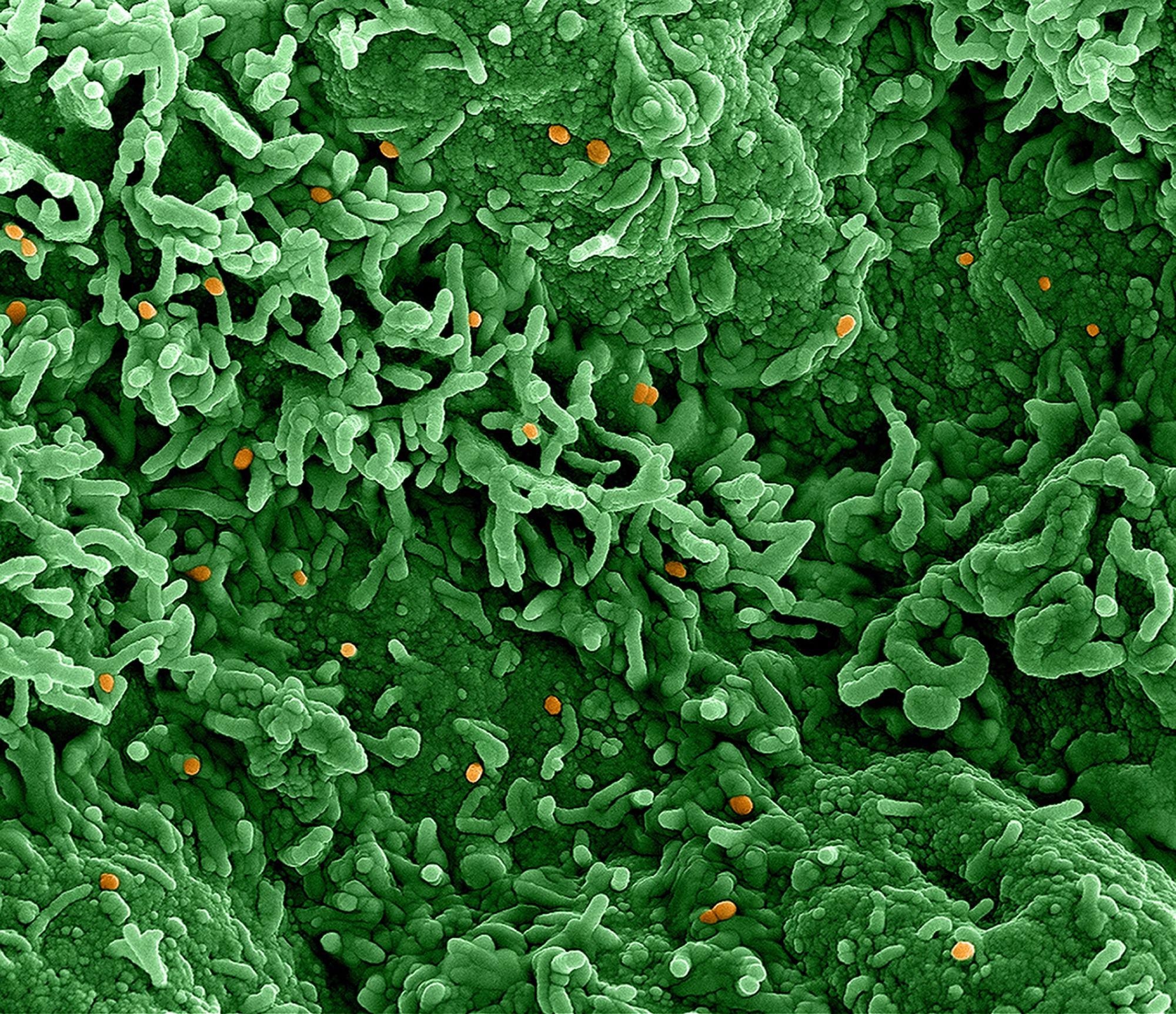

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of monkeypox virus (orange) on the surface of infected VERO E6 cells (green). Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of monkeypox virus (orange) on the surface of infected VERO E6 cells (green). Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for monkeypox infection. Management aims at ameliorating symptoms and supportive care. This may also involve treating secondary bacterial infections in complicated cases.

In 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tecovirimat, which is also known as TPOXX or ST-246, for the treatment of human smallpox disease caused by Variola virus in both adults and children. Although tecovirimat has not been approved to treat other orthopoxviral infections, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) allows this agent to be used to treat non-variola orthopox infections, including monkeypox, in both adults and children of all age who are at high risk of severe disease or are currently experiencing severe complications of this infection.

Prevention

Preventive measures should target limiting contact with rodents, prohibiting direct exposure to blood and body fluids and uncooked meats, halting bushmeat trade, and spreading awareness of the risks of consuming wild animals.

Robust health awareness efforts are required, and reinstating protective equipment use among susceptible populations is essential. In addition, infection control measures are of utmost importance, especially for healthcare professionals, along with immunization against smallpox.

Suspected cases must be isolated in a negative air pressure isolation room. Furthermore, contact and droplet precautions are also necessary.

References

- Petersen, E., Kantele, A., Koopmans, M., et al. (2019). Human Monkeypox. Infectious Disease Clinics Of North America. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0891552019300170

- Monkeypox FAQ: How is it transmitted? Where did it come from? What are the symptoms? Does smallpox vaccine prevent it? [Online]. Available from: https://theconversation.com/monkeypox-faq-how-is-it-transmitted-where-did-it-come-from-what-are-the-symptoms-does-smallpox-vaccine-prevent-it-184309.

- Kozlov, M. (2022). Monkeypox vaccination begins – can the global outbreaks be contained? Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-01587.-1.

- Multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries [Online]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON385#:~:text=Monkeypox%20endemic%20countries%20are%3A%20Benin,Sierra%20Leone%2C%20and%20South%20Sudan.

- Tecovirimat [Online]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html#:~:text=Tecovirimat%20(also%20known%20as%20TPOXX,not%20approved%20by%20the%20FDA..

Further Reading

- All Monkeypox Content

- What is Monkeypox?

- Monkeypox Epidemiology

- Monkeypox 2003 U.S. Outbreak

- Monkeypox Symptoms and Treatment

Last Updated: Jun 9, 2022

Written by

Nidhi Saha

I am a medical content writer and editor. My interests lie in public health awareness and medical communication. I have worked as a clinical dentist and as a consultant research writer in an Indian medical publishing house. It is my constant endeavor is to update knowledge on newer treatment modalities relating to various medical fields. I have also aided in proofreading and publication of manuscripts in accredited medical journals. I like to sketch, read and listen to music in my leisure time.

Source: Read Full Article