‘To walk in the beauty way’: Treating opioid use disorder in Native communities

Successful treatment for opioid use disorder addresses the whole person. Nowhere is this approach more important than among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities.

Native communities have been deeply affected by the opioid crisis, and many have been overwhelmed by opioid overdoses, deaths, and a strained healthcare system. Yet Native cultures’ ancestral strengths and healing traditions may also provide unique insights into the successful integration of treatment for opioid use disorder in primary care and addiction treatment clinics serving AI/AN people.

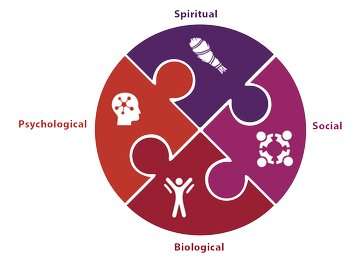

“We think of addiction as a brain disease, and that is a great way to reduce stigma and help people get the treatment they need. But putting the brain at the center of everything is a narrow way of thinking,” said Kamilla Venner, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of New Mexico and member of the Ahtna Athabascan Tribe. “We need a more holistic view that goes beyond a person’s biology. We must integrate culture, societal factors, and even spirituality, when appropriate, into mainstream medical institutions and education.”

Funded through the Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM Initiative, or NIH HEAL InitiativeSM, and co-led by Venner, a new study’s “two-eyed seeing” approach uses both Western and indigenous worldviews. Its goal is to create an evidence-based, sustainable, and culturally centered intervention to support programs serving AI/AN people who have opioid use disorder (OUD). The 4-year project will advance HEAL’s research on overcoming barriers to treatment for people with OUD.

American Indians and Alaska Natives had the second-highest rate of opioid overdose out of all U.S. racial and ethnic groups in 2017, and the second and third highest overdose death rates from heroin and synthetic opioids, respectively, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

A cornerstone of the project is an 18-member collaborative board formed by tribal leaders and Elders, OUD treatment providers in tribal communities, researchers, including an ethnobotanist (an expert in local use native plants), and people who are in recovery from OUD. The board meets monthly with the HEAL researchers, and in smaller work groups, to plan the creation, adaptation, and testing of the research intervention.

“I’m excited about the energy and commitment of the board members,” said Aimee Campbell, Ph.D., M.S.W., study co-lead, associate professor of clinical psychiatric social work at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and research scientist at New York State Psychiatric Institute. “They are thinking deeply and authentically about the opioid problem and how to help their communities.”

New ways of thinking about OUD treatment

Native communities face unique risk factors for OUD.

“Discrimination, historical trauma, stigma, a lack of resources, and workforce shortages have all contributed to the crisis among Native communities,” said Melanie Nadeau, Ph.D., M.P.H., assistant professor and assistant director for the public health program at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences. Nadeau is a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and is one of the board’s four co-chairs.

Although Native communities face many challenges, they also have strengths that can help people achieve recovery—such as strong family and community ties, Tribal sovereignty, and hard-earned resilience.

Standard treatment for OUD usually focuses on the individual, but Native peoples often approach health and wellness more holistically. This disconnect makes it challenging to incorporate aspects of community and family traditional practices—essential and strengthening elements of Native culture—into mainstream medical treatment.

“Being well, for a Native person, means being balanced in terms of physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health. In addition, the person would be in good relationships with their community and with their relatives,” Nadeau said.

Collaborative intervention design

The researchers are selecting two urban and two rural sites for the study. Each rural site will work with primarily one Tribe, while the urban sites may serve people from dozens of Tribes. The goal is to integrate medication-based treatment into primary health care and addiction treatment settings in a culturally appropriate way that serves Native people.

“For each site, we’ll first identify the current strengths, resources, and needs,” said Campbell. “We’ll also find out about staff who will be able to carry out the project, and we’ll identify a champion at the site to provide leadership. By involving Tribal communities in the research from the beginning, we help ensure that the intervention will be sustainable, since it came from the community.”

Venner and Campbell envision that several different Tribal practices could serve as foundations for a culturally centered intervention. For example, there may be opportunities to build on traditional practices, such as beading or drum making, and sweat-lodge ceremonies, as well as Tribal medicines, Campbell said.

“We could help people seeking treatment think about being in balance, or ‘walking in the beauty way,’ as Navajo people say,” added Venner.

Researchers could explain that Western science shows medication treatment is an effective tool to help people function better and achieve their goals, Venner suggested, and “also acknowledge that people might want to avail themselves of other solutions, whether that’s getting back in touch with their cultural identity or their spiritual side or using traditional medicines,” she said.

At the end of the study, the researchers and collaborative board hope to have a menu of traditional practices that could be integrated with medication-based treatment for different Native groups to help people achieve recovery.

Nadeau dreams that one day, people struggling with addiction will have access to land-based healing. For example, in addition to effective medication-based treatments, “people could gather medicine from the land, hunt and process their own food, build sweat lodges, and engage in ceremonies,” she said.

The researchers also hope that the study will lead to a successful culturally centered intervention, and that this more holistic approach will hold lessons for other indigenous communities and even mainstream society, Venner explained.

“We need to think about what leads to opioid misuse in the first place and then use every means available to help people recover, develop successful coping skills, and recreate their lives with more meaningful activities that don’t involve alcohol or drugs,” Venner said.

Source: Read Full Article