What makes the delta variant of COVID-19 so contagious?

The delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 has swept the planet, becoming the dominant variant within just a few months. A new study from Boston Children’s Hospital, published in Science, explains why delta spreads so easily and infects people so quickly. It also suggests a more targeted strategy for developing next-generation COVID-19 vaccines and treatments.

Last spring, study leader Bing Chen, Ph.D., showed how several earlier SARS-CoV-2 variants (alpha, beta, G614) became more infectious than the original virus. Each variant acquired a genetic change that stabilized the spike protein on the virus’s surface, the protein on which current vaccines are based.

But the delta variant, which emerged soon after, is the most infectious variant known to date. Chen and colleagues set out to understand why.

“We thought there must something very different happening, because delta stands out among all the variants,” Chen says. “We found a property that we think accounts for its transmissibility and so far appears to be unique to delta.”

Fast fusion, rapid entry

For SARS-CoV-2 to infect our cells, its spikes must first attach to a receptor called ACE2. The spikes then dramatically change shape, folding in on themselves. This jackknifing motion fuses the virus’s outer membrane with the membrane of our cells, allow the virus to gain entry.

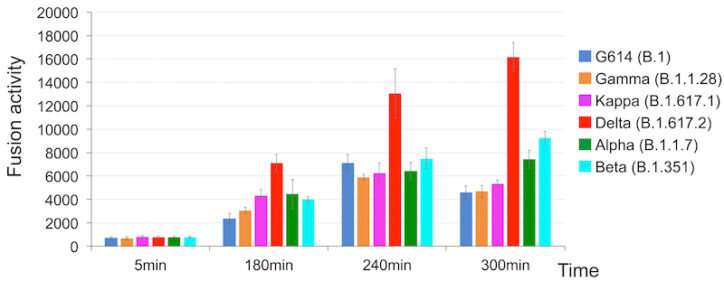

Using two kinds of cell-based assays, Chen and colleagues demonstrated that delta’s spike protein is especially adept at membrane fusion. This allowed a simulated delta virus to infect human cells much more quickly and efficiently than the other five SARS-CoV-2 variants. Delta had the advantage especially when cells had relatively low amounts of the ACE2 receptor.

“Membrane fusion requires a lot of energy and needs a catalyst,” explains Chen. “Among the different variants, delta stood out in its ability to catalyze membrane fusion. This explains why delta is transmitted much faster, why you can get it after a shorter exposure, and why it can infect more cells and produce such high viral loads in the body.”

Designing interventions, informed by structure

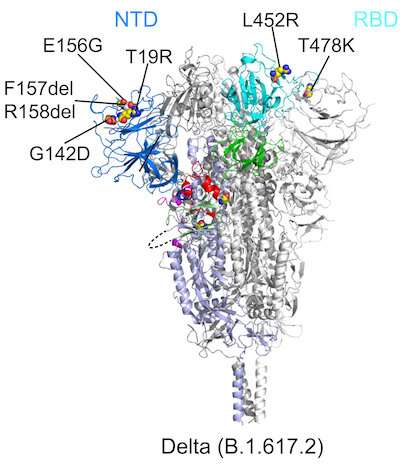

Chen and colleagues also investigated how mutations in the variants affect the spike protein’s structure. Using cryo-electron microscopy, which has resolution down to the atomic level, they imaged spike proteins from the delta, kappa, and gamma variants, and compared them to spikes from the previously characterized G614, alpha, and beta variants.

All six variants showed changes in two key parts of the spike protein that our immune system recognizes: the receptor-binding domain (RBD), which binds to the ACE2 receptor, and the N-terminal domain (NTD). Mutations in either domain can make our neutralizing antibodies less able to bind to the spike and contain the virus.

“The first thing we noticed about delta was that there was a large change in the NTD, which is responsible for its resistance to neutralizing antibodies,” Chen says. “The RBD also changed, but this led to little change in antibody resistance. Delta still remained sensitive to all the RBD-targeted antibodies that we tested.”

Looking at the other variants, the researchers found that each modified the NTD in different ways that altered its contours. The RBD was also mutated, but the changes were more limited. The RBD’s overall structure remained relatively stable across the variants, perhaps to preserve the spike’s ability to bind to the ACE2 receptor. The researchers therefore believe that the RBD is a more favorable target for the next generation of vaccines and antibody treatments.

Source: Read Full Article